The latest fear stalking biotech boardrooms isn’t a trial fail or an underwhelming funding haul, it’s the postman delivering a letter from the Nasdaq warning that the company’s stock faces delisting from the stock exchange.

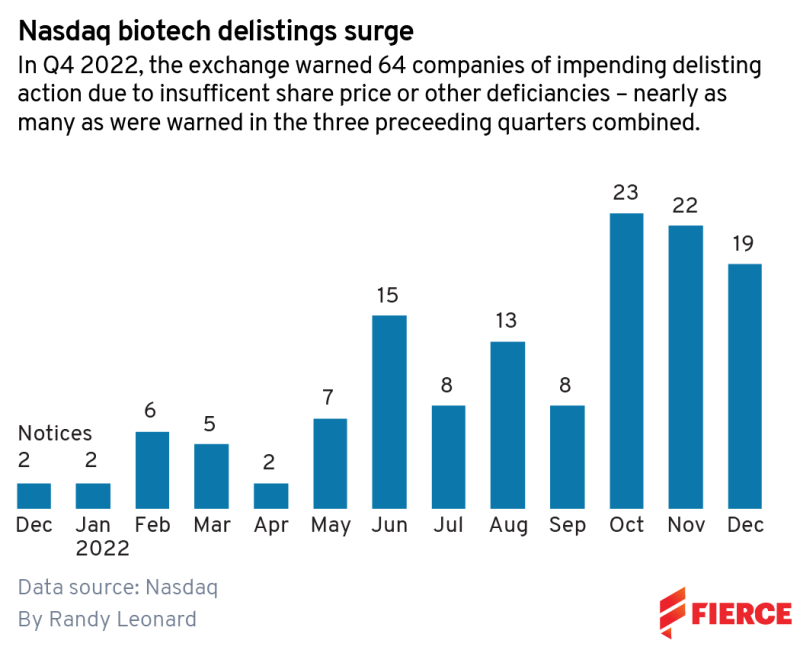

It seems to be an increasingly common occurrence. Nasdaq data show the number of drug developers warned that they could face delisting—a requirement if a company’s share price remains below $1—surged in the final months of last year. In October alone, 23 biotechs received the dreaded warning letter from the stock exchange.

While valuations of the largest pharma companies were saved from a “year of deep declines” by a rebound in the fourth quarter of 2022, biotechs remain in a “precarious” position, according to Evaluate Vantage’s latest report.

“Over the whole of the year, only a fifth of the 532 small-cap stocks ended up in positive territory,” the report’s authors wrote last month. “The large caps might have regained their mojo, but outside this group 2023 promises to be tough—floor or no floor.”

There certainly doesn’t appear to be any letup so far this year. After its phase 3 bladder cancer ambitions fizzled out, Sesen Bio revealed in January that it was facing delisting, using the news to justify the decision to merge with Carisma Therapeutics. In February, ObsEva preempted a delisting by laying off U.S. executives and retreating to Switzerland.

Kevin Eisele, managing director of equity capital markets at investment bank William Blair, attributed plummeting valuations across the sector to the inevitable crash after the biotech “sugar craze” of recent years.

“It's not a knock on the platforms or the science. It's really a question about the timing of when these went public,” he said in an interview. “There are many companies that went public that were frankly 18, 24 months out from an [investigational new drug application].”

“So when investors think about what's going to move this forward—do you want to leave your dollars in a company where there might not be any inflection point for the next two years?” Eisele adds. “Or are you going to reallocate those dollars to something that has a data event in the next three to four months?”

Not all biotechs have to take such drastic action. Some companies are able to climb their way back from the brink, including Addex Therapeutics. The Geneva-based biotech hit trouble when COVID-19 headwinds blew a trial of its allosteric modulator in Parkinson’s disease off course last June, sending the stock below the $1 mark. Soon, the letter from Nasdaq arrived on the doormat.

For CEO Tim Dyer, the first step was to calm investors.

“We have partnerships with Janssen and plenty of other reasons why investors should be bullish about the stock,” Dyer told Fierce Biotech in an interview. “Of course, when you disappoint on that lead asset, you've got to go out there and reassure them, tell them about what else is there and then rebuild a little bit of trust.”

Even when they are facing a looming delisting, biotechs still have time on their side. Nasdaq grants companies 180 days to make themselves compliant—in other words, to get their stock back above the $1 line—with the option of a further 180-day extension.

As well as the reputational hit, there are some practical downsides to being delisted. “What the bankers all told us was that the fact that you are no longer compliant [means] some funds can't buy your stock,” Dyer says. “So the bankers were very much encouraging us to go and sort it out ASAP.”

One increasingly common way that biotechs are avoiding delisting is to conduct a reverse stock split. This is where a company boosts its share price by reducing its number of outstanding shares by a set ratio—for example, swapping every two of its existing shares for one share. Dyer was advised to take this route.

“One of the reasons the banks wanted us to do it is they said, ‘If you do it, we can use it as a marketing tool to raise your capital,’” he explains. “You've seen a lot of companies doing it and raising capital off the back of it.”

No biotech ever really dies from dilution, they die from a lack of funding." – Kevin Eisele, William Blair

However, depending on your arrangement with your deposit bank, a reverse stock split can entail some “quite hefty fees,” Dyer says. “That’s something we didn’t want to spend.”

For companies who do go down the reverse stock split route, it’s not necessarily a bad thing, according to William Blair’s Eisele.

“No biotech ever really dies from dilution, they die from a lack of funding,” he says. “Whether it’s delisting to save on expenses [or] moving to over-the-counter exchanges to save on those regulatory and listing exchange costs, just to be able to fund an additional quarter or two to get you to that data point that you need to really drive the company forward.”

Rather than condensing its stock, Addex’s approach was all about clear, positive communication to investors about the company’s other “high value” programs as well as how they were going to “tighten up the cash burn,” Dyer says. “I went out to a few conferences, but not very many. Really, it was just to keep reiterating that message every time we came up with the financial results announcement.”

“Now, I haven't yet delivered the deal that I'm promising everybody,” he admits. “But I think people see the portfolio, they've seen our track record of doing deals and they believe that it's doable.”

While this hearts and minds strategy didn’t nudge the stock price immediately, Addex’s shares began to recover at the start of this year, coinciding nicely with the on-schedule completion of recruitment for Janssen’s phase 2 study of Addex’s epilepsy treatment ADX71149. The biotech's shares are now worth $1.20, after hitting a low of 55 cents apiece just before Christmas.

For biotech executives losing sleep over their own stuttering stock price, Dyer’s relaxed attitude to potential delisting may offer some reassurance: “It's not a big deal if you fundamentally believe in your business and your strategy.”

“The markets are what the markets are. What we've seen over the last decade is this huge disconnect between real value and stock prices, because prices are driven by buyer and seller demand,” the CEO adds. “So we just continue to focus on the long game.”

Max Bayer and Annalee Armstrong contributed to this article.