And just like that, we have a crowded race to be the first approved nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) treatment—a market that could grow to $108.4 billion globally by 2030.

Terns Pharmaceuticals revealed data Tuesday evening showing that TERN-501 reduced liver fat by 45% in the high dose arm of a phase 2a trial after 12 weeks, compared to 4% in the placebo group. The readout follows clinical success from peers Madrigal Pharmaceuticals and Viking Therapeutics, which are both developing therapies with the same mechanism of action as Terns’ candidate—but both are much further ahead in the clinical timeline.

These biotech breakouts follow years of failure and abandoned assets. Big Pharma once had a foothold in the clinic but mostly walked away. Now, the rise of GLP-1 obesity meds has reinvigorated major companies' interest, as has Madrigal's submission of a rolling review for resmetirom to the FDA.

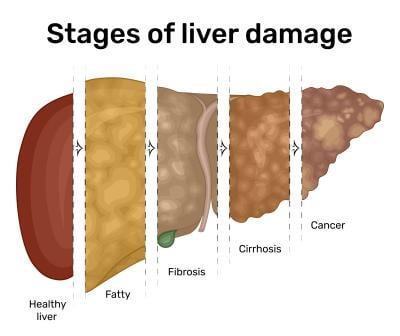

NASH is a type of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) that results in liver inflammation and damage due to the accumulation of fat. This can result in fibrosis, or liver scarring, and potentially lead to irreversible damage known as cirrhosis, which in turn can increase the risk of developing liver cancer.

NASH is one of the leading causes of liver transplantation. The condition mostly affects people with related conditions like obesity or diabetes, with research suggesting that 75% of people who are overweight have NAFLD.

Who will be first?

There are currently no approved therapies for NASH, but 84 treatments are in the biopharma pipeline, according to a new analysis from Global Data. Only four of those, or 5%, are in phase 3 development, including Madrigal’s resmetirom. More than half of all potential NASH medicines are in phase 1, preclinical development or still in discovery.

Madrigal reported a second positive phase 3 readout in December 2022, showing that resmetirom hit both liver histological improvement endpoints that the FDA had proposed as reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit. Liver biopsies were conducted to collect the data, which is a difficult way to conduct a trial, but one the company says is the best way to show the improvements from the medicine. In the study, 26% of patients on the 80-mg dose and 30% on 100 mg, respectively, achieved the primary endpoint of a reduction in the NASH activity score—which includes ballooning and inflammation—of two or more points as well as no worsening of fibrosis.

Resmetirom also led to a 24% and 26% improvement in the second primary endpoint measuring fibrosis in the low and high dose groups, respectively. This compares to 10% and 14% for the two primary endpoints in the placebo arm.

Analysts agree that Madrigal will make it to the market first. The company has already submitted an application to the FDA on a rolling basis for an accelerated approval. Mizuho analysts have previously estimated that Madrigal could see $1 billion in peak sales as the first mover in the indication.

Then there’s Viking, which is sailing behind Madrigal in a midstage study. The company linked VK2809 to mean relative changes in liver fat of up to 51.7% without causing widespread gastrointestinal side effects. But Viking will need to show success on the histological improvement endpoints like Madrigal has for resmetirom, as these are the trial goals the FDA is looking to for approvability. Viking is currently conducting a second phase 2b trial with 52 weeks of follow-up to assess this endpoint, as the initial trial just showed 12 weeks’ worth of data.

Viking recently reported in a second-quarter earnings update that if the phase 2b results are positive—the readout is expected in the first half of 2024—the company will schedule a meeting with the FDA to discuss the phase 3 program.

Terns, on the other hand, has some big decisions to make following the phase 2a readout. Mizuho urged the company to take its time to consider whether independent development makes sense or whether a partnership can be established to fund the likely “large and expensive study” to come. The company intends to run a phase 2b.

“We're supportive of TERN taking its time, as in our view, a well-thought-out clinical plan and development strategy (e.g., on which combination, whether to partner), especially at this stage, is certainly warranted,” Mizuho said.

Some other participants in the NASH clinical scene are Boston Pharmaceuticals, which just showed a former Novartis drug led to a 50% or greater reduction in liver fat on an exploratory efficacy endpoint in a phase 2a study. Akero Therapeutics and 89bio also have rivals coming up.

One company no longer in the running is Intercept Pharmaceuticals, which received a complete response letter from the FDA for its farnesoid X receptor agonist Ocaliva, or obeticholic acid, in June. The company had been seeking approval for the second time to treat patients with NASH who have stage 2 or 3 liver fibrosis. Now, Intercept has discontinued all NASH work, leaving Ocaliva approved for primary biliary cholangitis.

The Intercept failure sent a chill through the NASH scene, but with strong data, Viking and Madrigal have managed to sail on. Vantage estimates the market was worth $2.5 billion in the U.S. in 2022 and could grow to $108.4 billion globally by 2030.

Had Intercept made it to the market ahead of Madrigal, the latter still would have had the leg up, as the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) backed the cost-effectiveness of resmetiromin in a February draft assessment. ICER said an annual placeholder price of $19,000 for resmetirom would provide cost savings over a lifetime of care for NASH patients. Ocaliva’s current list price of $85,000, however, would need to be reduced dramatically to make it cost-effective.

What about GLP-1s?

Just as the biotechs put down their markers in NASH, the Big Pharmas came back to the table—albeit through a roundabout way. The most exciting thing in pharma right now is the red-hot obesity market, and it turns out those megablockbusters in the making could also lower liver fat.

Mizuho called the emergence of GLP-1s a “significant bear thesis weighing over the NASH space.” But while they can lower weight, these therapies still don’t address the major problem with NASH, which is liver damage.

“In our view, while treatment with a GLP-1 may lead to significant weight loss (and thus improved metabolic disease outcomes), GLP-1s have little/no impact on fibrosis and inflammation in the liver; given this, and also, in consideration of GI adverse events for GLP-1s can often be quite problematic, we don't currently envision a scenario whereby GLP-1s completely obviate the need for other products and mechanisms of action in the treatment paradigm for NASH,” Mizuho’s Graig Suvannavejh, Ph.D., and Avantika Joshi wrote in a Wednesday morning note.

Novo Nordisk’s GLP-1 obesity juggernaut semaglutide, known as Wegovy when marketed for weight loss or Ozempic for diabetes, could not outdo placebo in a phase 2 study for NASH, according to results posted in June 2022. But the company is plugging forward in a phase 3 trial. The Danish pharma also has three meds for the indication in the pipeline across phase 1 and 2.

Merck, trying to take on the industry leader, showed that its dual GLP-1/glucagon receptor co-agonist efinopegdutide was better than semaglutide in the related disorder NAFLD in June. The Merck therapy posted a 72.7% mean reduction in liver fat content at Week 24 compared to 42.3% for the Novo Nordisk med. Analysts, however, noted that Merck tested a smaller dose of semaglutide than is standard.

Eli Lilly is also testing Mounjaro in NASH, a therapy currently approved for diabetes and under review for obesity.

Rather than shrink back from the impending challenge, the biotechs are seeing opportunities to work together through combination approaches that could address the disease from all sides.

Terns could see TERN-501 become “a potential backbone for future combination treatment of NASH,” according to Mizuho.

As all of these factors converge, Global Data says deal activity in the space could heat up. Madrigal has for at least the past year been the discussion of increasingly intense M&A talks. Big Pharma could seek to take a bigger stake in future NASH combination regimens.

“While most assets have suffered the same fate as Intercept’s [Ocaliva], these attempts have fueled a certain degree of M&A and strategic alliance deal activity between 2018 and 2022,” Global Data’s Sravani Meka, senior immunology analyst, said in the report. “However … M&A and strategic alliance deal activity remained relatively flat during that period, potentially due to the high proportion of agents in the early stages of development.”

Venture interest in the space has been decreasing, but Global Data suspects that’s due to outside forces like the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation and other macroeconomic environment factors and is not reflective of the potential market opportunity.

“With the slow recovery of the pharma/biotech markets, in addition to the increasing therapeutic potential of combination treatments, it is possible that investments in the pharma/biotech space may continue to see a flat growth rate in the short term,” Sravani wrote. “However, it is anticipated that the trend might be reversed with ongoing developments within the NASH pipeline landscape. As the market becomes more saturated, and companies are able to capitalize on clinical trial data, it is likely that late stage partnering activity will begin to rise.”