Edwards Lifesciences has secured European approval for its transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement system, which the company described as the first minimally invasive therapy of its kind to receive a regulatory green light.

Separating the right ventricle and atrium, a leaky tricuspid valve with its three or more moving flaps has proven to be a difficult fix compared to the cardiac muscle’s mitral and aortic valves.

Variations in the tricuspid valve’s anatomy have also posed challenges in open heart surgery—a risky procedure limited to certain situations in cardiology guidelines—as patients also commonly suffer from congestive right-side heart failure.

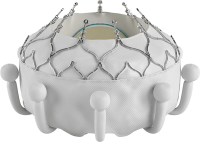

According to Edwards, the self-expanding Evoque implant is designed to fully replace the heart’s native tricuspid valve and eliminate the backflow of blood known as regurgitation, which can cause debilitating or life-threatening symptoms.

The device’s new CE mark allows it to be sold on the continent alongside the company’s Pascal system, a clip-like device that holds the tricuspid valve’s flaps together to form a tighter seal, and the Cardioband, which helps reshape and strengthen the outer ring structure of the valve. The devices in Edwards’ transcatheter tricuspid portfolio have yet to obtain approvals from the FDA.

In a previously reported single-arm study, 90.1% of patients survived the first year following an Evoque procedure, while 88.4% were able to avoid rehospitalizations due to heart failure, and 97.6% saw sustained reductions in their levels of tricuspid regurgitation.

The company said it plans to present results from a subsequent randomized, pivotal trial during a late-breaking session at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics symposium in San Francisco next week.

Earlier this year, Abbott delivered clinical data on its potential competitor implant, the TriClip—which takes a similar approach as the company’s top-selling MitraClip implant and Edwards’ Pascal device—with a randomized trial exploring percutaneous tricuspid transcatheter edge-to-edge repair in severe cases of regurgitation, a procedure known as TEER.

Published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the results showed the procedure was safe, reduced the severity of tricuspid leaks and led to improvements in quality of life. However, the rate of deaths, open surgeries and heart failure hospitalizations did not appear to differ when compared to a control group receiving medical therapies such as diuretic medications. Abbott also plans to present late-breaking data from the study at the TCT symposium.