In a milestone that could turn sci-fi into fact, the first U.S. clinical trial of a brain implant that returns the power of communication to severely paralyzed people has begun.

Synchron’s Stentrode system was implanted in the trial’s first participant at Mount Sinai West hospital in New York City, the company announced Tuesday, kicking off an FDA-authorized study of a device that aims to convert the thoughts of people with paralysis into actions.

Unlike other proposed brain-computer interfaces, Synchron’s BCI technology doesn’t require open-brain surgery or any drilling into the skull. Instead, it can be put in place in a minimally invasive surgery that takes only about two hours.

“The implantation procedure went extremely well, and the patient was able to go home 48 hours after the surgery,” said Shahram Majidi, M.D., the Mount Sinai neurointerventional surgeon who performed the procedure.

The U.S. clinical trial—which nabbed investigational device exemption from the FDA a year ago—will ultimately include six participants. It’s supported in part by a $10 million grant from the National Institutes of Health’s Neural Interfaces Program.

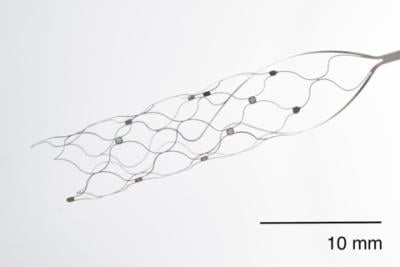

As the name suggests, the Stentrode system centers on a permanently implanted stent-like device. It’s inserted through the jugular vein to reach the motor cortex of the brain, where it can pick up neurological signals denoting an individual’s intended actions.

Synchron’s BrainOS technology platform collects those signals from a receiver unit implanted in the user’s chest, then translates them in real time into clicks and keystrokes on a computer or mobile device. An additional eye-tracking device is used to control the movements of the computer cursor.

The intended result is a system that allows people with severe paralysis to send texts and emails, access online banking and shopping services, complete telehealth visits and more, all using only their thoughts to control the tech—therefore returning some independence to their lives.

The Command trial will specifically measure the safety of the implant, as well as the ability of the Stentrode system to help participants control their digital devices hands-free and improve their functional independence.

The technology has already proven effective in an Australia-based study. The Switch trial launched in 2019 and eventually grew to include a total of four participants, all of whom were paralyzed from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS.

As described in one-year data published earlier this year, the implant stayed in place for the entire first year for all patients and didn’t cause any adverse events leading to disability or death. The participants were also able to successfully control digital devices hands-free—a feat that included the sending of the first tweet posted via direct thought last December.

Overall, the participants were able to reach typing speeds of at least 14 characters per minute without the help of predictive text technology. They also achieved more than 90% accuracy in controlling cursor clicks through the system.